Anyone looking through a telescope for the first time soon discovers that it is not the tube but the eyepiece that determines what the image looks like. The eyepiece is the last piece of optics between you and the universe; it translates the captured light into a sharp, contrasty and comfortable image. In this telescope eyepiece explanation we dive into what distinguishes a good eyepiece from a mediocre one: focal length, field of view, eye relief, glass quality and the balance between magnification and brightness.

This is how you calculate what you can actually see

After you know what size eyepiece fits your telescope, comes the most important piece: understanding what each eyepiece actually shows. The focal length of an eyepiece determines not only how “far in” you look, but also how clear the image remains. This is where the concept of target planning around the corner: cleverly combining magnification and brightness to make visible exactly what you want to see.

Magnification is calculated using a simple formula:

Magnification = focal length telescope ÷ focal length eyepiece.

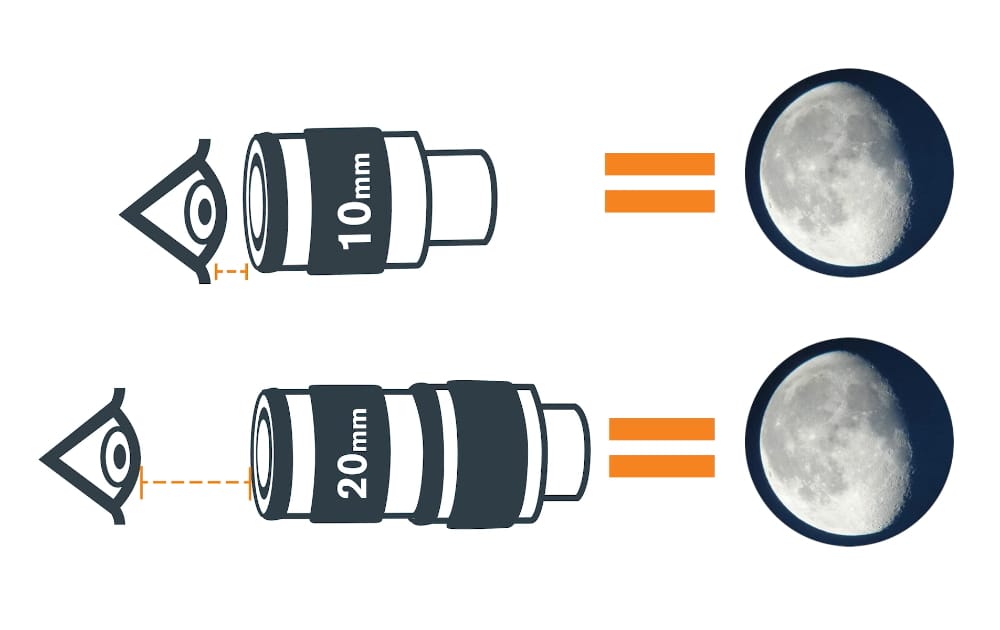

Thus, a telescope with a focal length of 1000 mm and a 10 mm eyepiece provides 100× magnification. If you choose a 25 mm eyepiece, the magnification drops to 40× - the image becomes brighter and clearer.

The brightness is directly related to the exit pupil, the diameter of the light beam leaving the eyepiece. You calculate this as:

Exit pupil = aperture (mm) ÷ magnification or = eyepiece focal length ÷ f-number of telescope.

Thus, a short eyepiece with small focal length produces a small exit pupil (darker, more detail), while a long eyepiece produces a larger exit pupil (brighter, wider image). Those who understand how these values work together can optimize any telescope for a variety of purposes: from the rings of Saturn to the faint nebulae in Orion.

AFOV and TFOV: how wide you really see

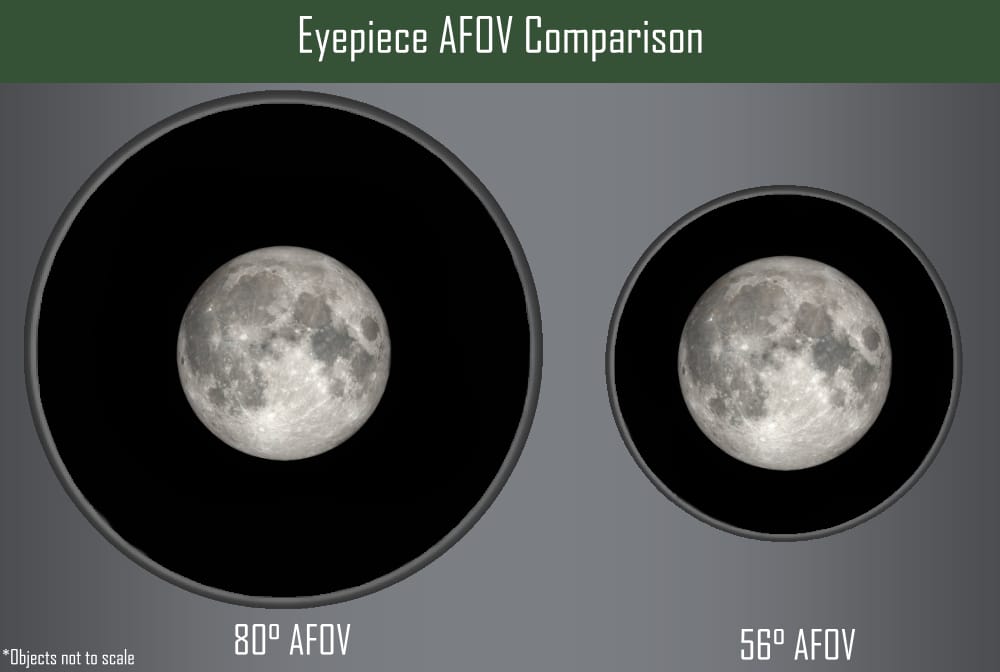

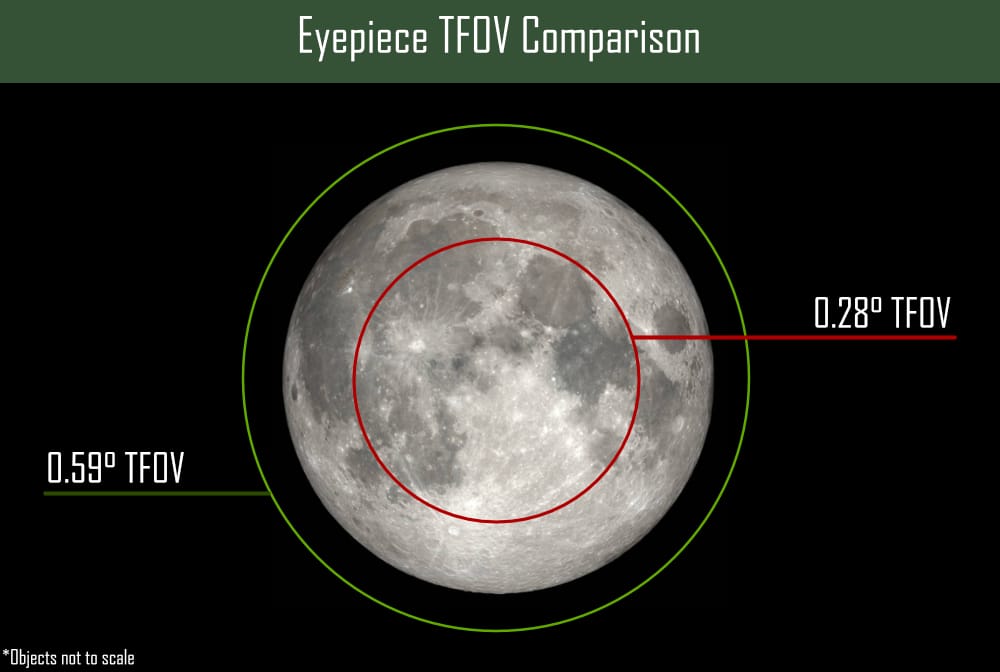

Field of view is what makes perception spatial. Eyepieces have a apparent field of view (AFOV), the apparent field of view experienced by your eye, measured in degrees and a true field of view (TFOV), the actual angle of sky you see. AFOV tells how immersive it feels: a 50° eyepiece gives a classic round window; 82° or more feels like you're in it.

TFOV is easily calculated with TFOV = AFOV ÷ magnification. Suppose you pair a 2032 mm telescope with a 7 mm eyepiece with an AFOV of 82°. The magnification is 290× and so the TFOV is 0.28°. That's just over half the lunar disc. Those who want to see the moon fully in focus thus need a TFOV greater than 0.5°, and thus a longer focal point or wider eyepiece.

The role of magnification in choosing objects - from open clusters to planetary details

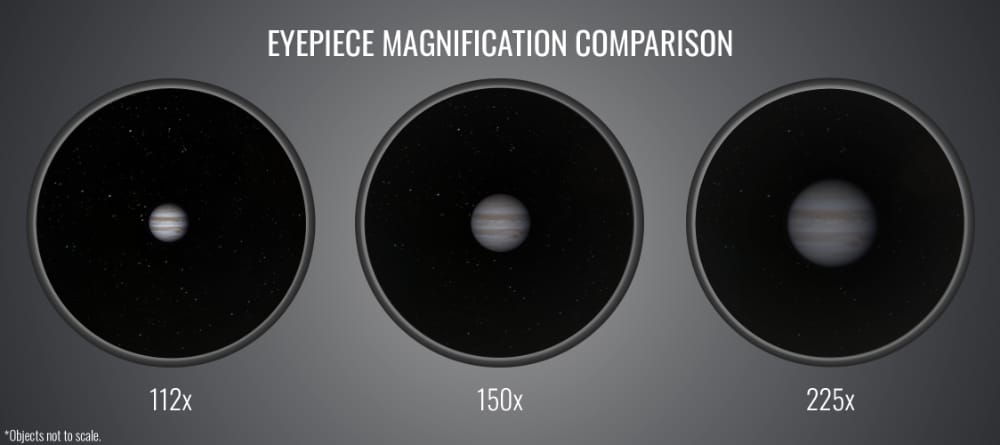

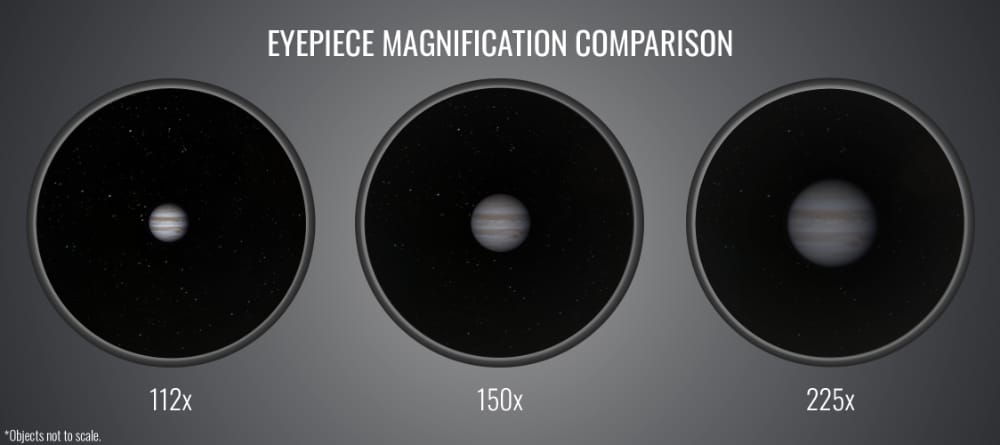

Magnification determines how large an object appears in your field of view, but also how useful that image remains. Higher magnifications magnify not only the object, but also any irregularity in the sky, spreading the available light over a larger area. As a result, the image brightness drops rapidly as you “zoom in” further.

A handy way to picture it is with a flashlight on a wall. If you aim a narrow beam, the spot is small but intensely bright. Widen the beam, and the image becomes larger but much weaker. The same goes for your telescope: double the magnification, and the brightness decreases by a factor of four.

Use that knowledge to plan purposefully. With a 8-inch telescope (about 200 mm aperture) you can roughly use the following ranges: low magnifications of 30× to 70× show open clusters and galaxy fields in their full context; medium magnifications around 100× to 150× bring nebulae and galaxies closer; high magnifications of 200× to 300× reveal the finest details on the moon or the cloud bands of Jupiter.

A larger aperture captures more light and compensates for the loss of brightness at high magnification, so larger telescopes not only “zoom in more” but more importantly retain more light and contrast at the same eyepiece. But to be perfectly honest, for planets you already have enough with 100 to 150x magnification with a good quality eyepiece.

Optical quality and coatings

The sharpness you see is never better than the weakest piece of glass in your optical chain. Cheap eyepieces often have simple lenses with few layers of coating; these reflect light and reduce contrast. Good quality eyepieces use ED or lanthanum glass that corrects color deviations and allows more light through.

Also important are the coatings: FMC (fully multi-coated) lenses minimize reflections and increase light transmission to above 95 %. In more expensive eyepieces, the lens edges are additionally painted black (blackened edges) to suppress stray light and internal reflections. That seems like detail work, but you see the difference immediately on planets and the moon: more microcontrast, more calmness in the image.

Eye relief: looking without peering

Eye relief is the distance between your eye and the eyepiece at which you see the full field. Short eye relief feels like you have to press your eye into the glass, and that's tiring, especially with glasses. 15 mm or more is comfortable for most observers; 20 mm is ideal for eyeglass wearers. Some series, such as the “long eye relief” designs, maintain that comfort even at short focal lengths.

Visions and balance

The 1.25″ eyepieces are the most common. They are compact, inexpensive and fit virtually any telescope. They often have shorter focal points, making them ideal for planetary and lunar observations. 2″ eyepieces are larger, heavier and more expensive, but can combine longer focal lengths with a wide field of view, perfect for vast nebulae, open clusters and galaxy fields. Do pay attention to balance: with Dobsonians, a heavy 2″ eyepiece can shift the balance.

Magnification, brightness and exit pupil

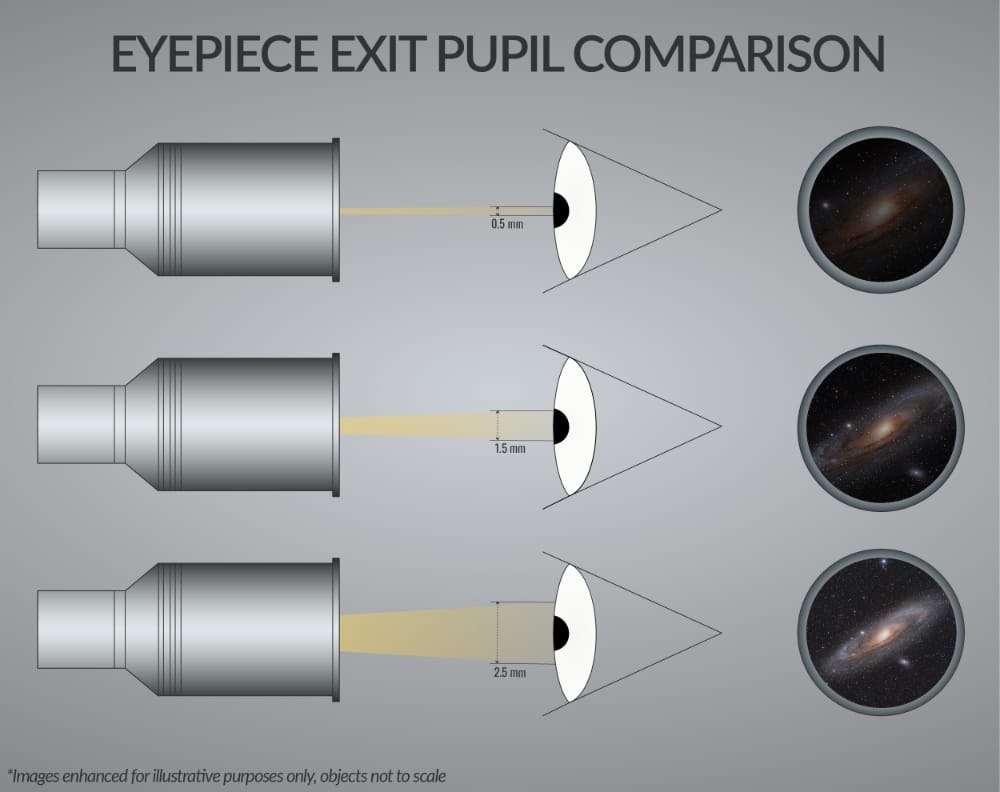

Behind every well-chosen eyepiece is one figure that is often overlooked: the exit pupil. That is literally the disc of light that comes out of the eyepiece and enters your eye. The diameter of that disc determines how much light and detail you actually see.

The calculation is simple:

Exit pupil = aperture (mm) ÷ magnification or = eyepiece focal length ÷ f number. The f value = focal length + aperture.

With a 200 mm telescope at f/10 and a 10 mm eyepiece, you get a magnification of 200× and an exit pupil of 1 mm, ideal for planets. With a 25 mm eyepiece, the magnification drops to 80× and the exit pupil rises to 2.5 mm, a perfect balance for most deep-sky objects.

In practice, it works like this: an exit pupil of 0.5 to 1 mm is suitable for moon and planets, where brightness is not an issue. Round 1 to 2.5 mm globular clusters perform best. Between 2 and 3 mm planetary nebulae stand out because of bright contrast, while a 3 to 7 mm exit pupil is ideal for wide objects such as the Andromeda Nebula or the Pleiades. The rule of thumb remains: around 2 mm lies the sweet spot for most observations, bright enough to see subtle details but still contrasty and calm in image.

Exit pupil and magnification always move in opposite directions. If you enlarge the image, you reduce the beam. If you double the magnification, then the exit pupil halves. This is exactly why eyepieces with extremely short focal lengths on small telescopes often disappoint: the image not only becomes darker, but also more sensitive to vibration and air turbulence.

Maximum magnification in practice - the line between sharp and meaningless

Even the best optics have a limit, and that limit rarely lies with the telescope itself. It is the atmosphere that determines how much magnification you can really use. Under average conditions, you can count on a practical limit of 40-50× per inch aperture. For an 8″ telescope (about 200 mm), that means a usable maximum around 300×.

The classic rule of 50-60× per inch is optimistic and only applies in perfect seeing, something that rarely happens in the Netherlands and Belgium. In practice, that high magnification usually produces a soft, shaky image without extra detail.

Again, take the 8″ Schmidt-Cassegrain with a focal length of 2032 mm.

With a 7-8 mm eyepiece you reach about 250-290× magnification, ideal for planetary and lunar craters. A 13-14 mm eyepiece gives about 150×, perfect for most deep-sky objects and good for planets. A 25-30 mm eyepiece drops to 70×, framing wide fields such as the Double Cluster or the Orion Nebula beautifully.

The secret is in the balance between magnification, brightness and atmosphere. On nights with calm seeing, you can push that limit and get the most out of your eyepieces. On restless nights, modest magnification often produces a sharper, more contrasty image.

Ocular types in practice

The Plössl design is the classic base: four lenses in two achromatic doublets. Cheap to produce, sharp image, but with a relatively narrow field of view (about 50°) and little eye relief at short focal lengths. Ideal for beginners or as a second eyepiece.

Wide-angle eyepieces extend that field to 68°, 82°, or even more. They contain more lens portions, but deliver an immersive experience ideal for deep-sky observation. Well-known examples are the Nagler or Panoptic types.

Zoom eyepieces combine multiple focal points in one housing. Useful if you want to quickly switch between magnifications without changing eyepieces each time, for example during public viewing evenings or variable seeing. Note that at the short end, the field of view and eye relief reduce noticeably.

Glass, protection and maintenance

An eyepiece is precision optics; take care of it that way. Store them in screw jars or a padded case, preferably with silica gel to reduce moisture. Clean them only when really necessary, excessive polishing wears down coatings. Use air blower, LensPen or microfiber cloth with special optical fluid. Avoid household detergents: they corrode the coating and create micro-scratches that cost contrast.

Smart combining for your telescope

A balanced set consists of three focal points: one for widescreen and search, one medium for most deep-sky objects, and one short focal point for planets. A quality barlow can double that set without losing quality. Add a moon or UHC filter and you have a versatile toolkit for any night.

Those who know how focal length, exit pupil and field of view work together will get the most out of their telescope - regardless of make or model.

View our eyepieces for any type of telescope, or read more in our selection guide for beginners To discover which magnifications best suit your goals.

- € 229,00 – € 269,00Price range: € 229,00 through € 269,00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

- € 275,00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page